Improving environmental outcomes

Every farm is unique, and so too is every plan to minimise environmental impact. Strategies that work for you may not work for your neighbour, and vice versa. With pastures, however, science has shown us even small changes can make a big difference.

Grow in winter

The wet winter-spring period is the main risk time for N leaching, so the more winter growth in the system, the more soil N is taken up. Modern plant breeding has really helped this - today’s perennial ryegrasses grow 20-30% more winter DM than their 20-year-old predecessors. To soak up even more N in winter, sow the highest yielding Italian or annual ryegrass (e.g. Tabu+ or Hogan) or cereal (e.g. Hattrick oats).

Cover up

Nothing loses soil N in winter like bare ground. Post autumn or winter crops, sow Catch-crop+ (a mix of oats and Italian ryegrass) to help catch any excess N before it has a chance to leach. Don’t wait till the whole paddock is bare – sow half as soon as the crop is grazed. Earlier sowing gives much better yield and N uptake.

Min till

It means more careful weed and pest control, but establishing new pasture through minimum tillage releases less N than cultivation, and also uses less diesel. Long term it is better for soil structure too.

Mix it up

Plantain and chicory can help reduce nitrogen leaching over diploid perennial ryegrass, because they contain more water than diploid perennial ryegrass, and thus dilute the nitrogen content of urine. Tetraploid ryegrasses also have potential here, for the same reason, plus they persist better and are easier to manage, boosting productivity in many farm systems.

Graze higher

Grazing at higher covers means we capture more of the sun’s energy. Typical diploid ryegrass pastures are grazed at around 2 - 2.5 leaves/tiller because this is the easiest way to maintain good residuals.

Better balanced grass

Alternatively you could grow the same amount of DM for 100 kg/ ha less N fertiliser (based on a growth response of 12 kg DM/kg N).

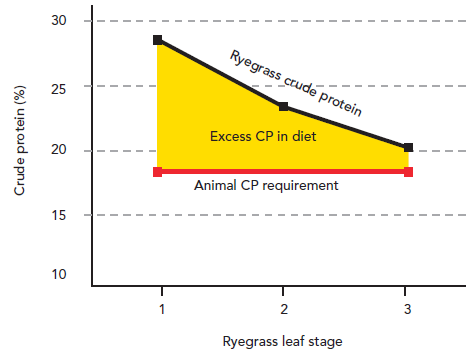

Grazing higher also improves the nutrient balance of pasture. As ryegrass grows, its crude protein (CP) or N level drops (see below). Lactating animals need about 18% CP in their diet, so a pasture with 22% protein at that time supplies 4% too much. This excess protein, excreted as urine and dung, is what causes problems with N loading of soils. Grazing 0.5 leaf/tiller later may reduce CP by 1.5%, dropping excess protein by over 30%. Currently this effect is not recognised in Overseer. Hopefully it will be in time, as it is significant.

Crude protein (CP) in ryegrass at each leaf stage vs requirement of lactating animal

Break later

Use 24 hour grazing to give cows a new paddock in the afternoon. Cows eat about 70% of their intake in the first half of the grazing. Putting them into a new paddock when ryegrass carbohydrate levels are highest and protein levels are lowest in the late afternoon means there’s less N going into them. 24 hour grazing has no effect on cow production compared with 12 hour grazing (and is easier with half as many stock shifting decisions too!)

Feed more efficiently

Raising animal intakes puts more energy into animal production and less into maintenance. Lincoln University Dairy Farm is a great example of this principle in action.

It went from 680 cows to 560 cows, but maintained similar MS production, using tetraploid/diploid ryegrass pastures with higher ME and palatability than straight diploids to help increase cow intake. Putting more feed into milk production and less into cow maintenance also lightens the farm’s environmental footprint. Plus, fewer replacement heifers are needed, further improving environmental performance.

The same principles hold for breeding ewes, cows or finishing stock. Higher production per animal or faster growth rates mean greater efficiency and a lower environmental footprint. See page 123 for an example of this with lamb finishing.

Fix for free

Legume-rich pastures need less artificial N fertiliser. Use high performance red, white and annual clovers, as they fix 25 kg atmospheric N/ha for every tonne of DM grown (and provide higher animal performance too).

%20-%20Fix%20for%20free%20-%20photo.png?height=343&width=593)

Prevent pugging

Compacted, waterlogged soils release more greenhouse gases than soils with healthy structure. They are more prone to runoff and soil loss, with overland flow of sediment, phosphorus (P) and faecal material to waterways. They require more tractor work for seedbed preparation and sowing, and more fertiliser to ensure growth of subsequent crop or grass growth.

Reduce bare soil

Soil bared out by over-grazing is at higher risk of erosion than soil protected by pasture plants, even on flat land. Maintaining vegetative ground cover through pasture maintains and improves soil organic matter and structure, and enhances biological activity.